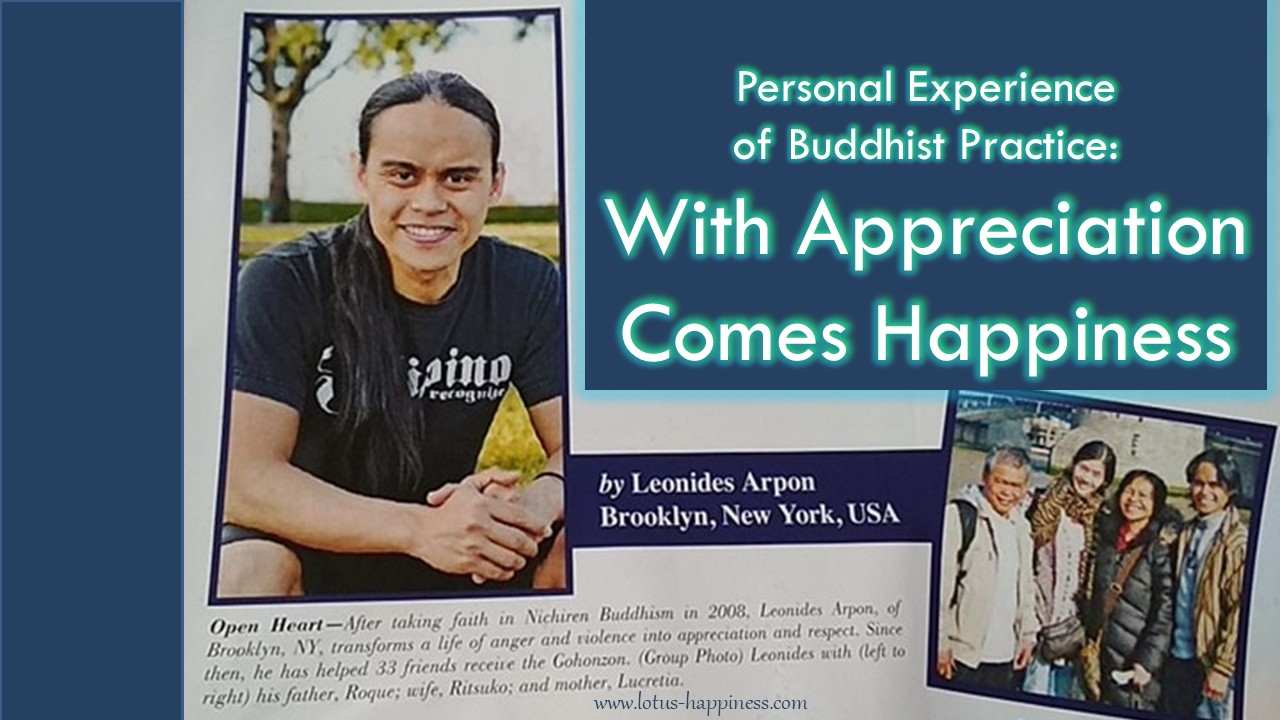

Personal Experience of Buddhist Practice: With Appreciation Comes Happiness

My parents left the Philippines for better work opportunities in Israel, and although I was born and raised there, the law denied me citizenship. Because of my Filipino ethnicity, I also dealt with racism daily. One of my more vivid memories as a child was sitting with my mother at a bus stop while a man spat towards us and yelled: “Dirty Filipinos.” Another time, I remember swimming in a public pool when a woman yelled: “Get that brown boy out of the pool, he is polluting it.”

My home should have been a safe haven, but instead my father “raised me by the belt”. This to me felt normal, but what really stayed with me was the verbal and mental abuse that I endured: “You are nothing. You are a piece of trash.” Worst of all, I believed it and grew angrier as the years went by.

One of the few people I trusted was a family that my parents worked for. They treated me like their own son. One of the family members was a famous dance teacher, and she personally mentored me and enrolled me in an acclaimed dance school. Dance became my way of proving my worth to myself and others.

Despite being an accomplished performer and teacher by age 18, I had to make a painful decision: leave Israel or risk being arrested and deported.

Up until I was 18, the government allowed me to live I the country as my mother’s dependent but once I became an adult, I was no longer allowed to work or live there. It was unfathomable that the place where I was born and considered home treated me as if I were an unwanted intruder. This injustice only added fuel to my already boiling anger.

At that time, in 1999, I moved to New York to continue pursuing my dreams as an artist. I successfully attained my work visa and toured the world with a major American dance company. But no matter how much success I had with my career on the outside, the anger I had developed growing up manifested in failed relationships with women and my family. No matter how positive I tried to think or even meditate, I kept seeing the same results.

After being invited to an SGI meeting in 2008, I remember feeling confused. I could not wrap my head around how people could be so happy despite facing personal challenges. At the same time, I was extremely inspired and moved by everyone’s life state, especially those who seemed to be suffering the most. My friend’s mother was dying of cancer but still his spirit was unshakable as he encouraged me ot practice Buddhism. Wanting to experience that kind of life condition, I received the Gohonzon six months later, on September 21, 2008.

After I started chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, I noticed how much I had let my environment affect my behavior. I also realized that my feelings of not being able to control my anger were related to my lack of worth and self-confidence.

The first thing I chanted to was to respect my own life and that of others, even those I inwardly begrudged. At the time, my parents were living in England, and they were both unemployed and risked deportation. My mother was also suffering with depression. When I shared Buddhism with them, my father became furious and threatened to disown me. Chanting to the Gohonzon, however, enabled me to recognise the positive qualities I inherited from my parents, which I was never able to see before. I summoned up the courage to express my deep respect and appreciation to them. Recognising a tremendous change in me, they were inspired to start chanting. They received the Gohonzon and joined the SGI-UK in August 2014. Today, my parents are British citizens and benefit from government housing. My mother also overcame her depression, and my father and I now have heart-to-heart dialogues.

Through chanting, I learned to fully appreciate my struggles, even my upbringing in Israel. As a result, I determined to create a dance outreach project at my former high school and show the SGI-USA “Victory Over Violence” exhibition there. The mission of my project was to share the importance of recognizing different types of violence in order to weed them out through dialogue, as well as the importance of people from diverse backgrounds uniting to take action for such a cause.

I did not have the funds for this project, so I chanted fiercely to make it happen. At this time, I shared the practice with a friend. Unexpectedly, he told his partner, who worked for an airline company, about my goals and offered me a buddy pass. Instead of paying $1,800 for economy class, I paid $500 for a round-trip ticket to Israel in business class.

My excitement was short-lived, though. Once I arrived in Israel to start the programme in the summer of 2011, the students I taught fought with one another and complained daily. They said things like: “Dance is useless, we already learn teamwork playing soccer,” or “This sucks; dance is stupid.”

But I refused to give up on my mission. At times when they tested my patience and I could feel my angry nature resurface, I consistently took action based on SGI President Ikeda’s guidance. Through that, I found the wisdom and courage to inspire the students, and the most difficult ones started to lead by example and became my greatest allies. By the end of the week-long programme, all 100 kids of Catholic, Jewish and Muslim backgrounds developed strong bonds of friendship, and the show was a total victory. The students kept asking if I could stay longer and when I’d be back.

I’ve learned that only when I change from within and recognise the unlimited potential in myself and others can I build a culture of peace anywhere at any time, starting with my immediate environment.

I am now happily married and determined to create an even more harmonious family, especially for my wife and me, and our future baby. Since I began practising seven years ago, I have helped 33 people receive the Gohonzon, including eight friends this year. I share Buddhism with everyone I know, because I really believe people can transform their lives and experience tremendous benefits. I also recognise and appreciate that we have freedom of religion in the US. In other countries, people can be persecuted or risk their lives for wanting to practise religion freely.

My mentor, President Ikeda, says: “Even if you have a kind heart, great ideas or wonderful aspirations, if you don’t have the courage to translate them into action, you’ll accomplish nothing with them. In fact, you’d be no different from someone who doesn’t have such things at all.”

With these words in my heart, my determination now is to develop my artistry and teaching skills, and use my experiences to enable people to discover their unlimited potential and contribute to society.

Source: World Tribune, SGI-USA, April 3, 2015